The current arrangement

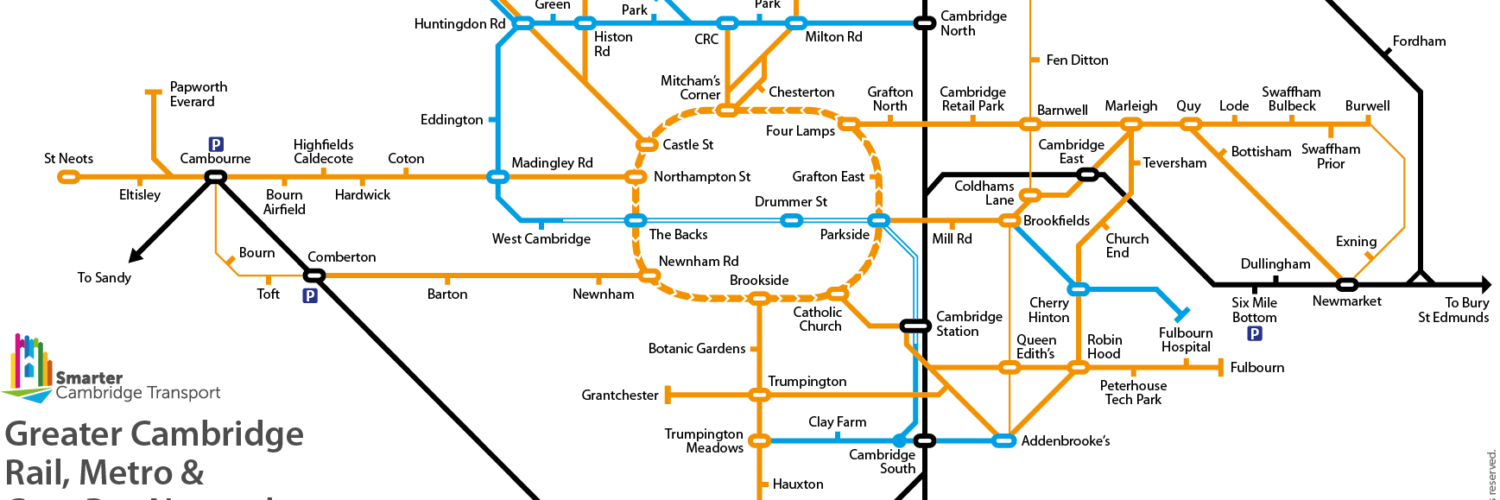

Cambridge has one central hub, and secondary hubs at Cambridge station and Addenbrooke’s hospital.

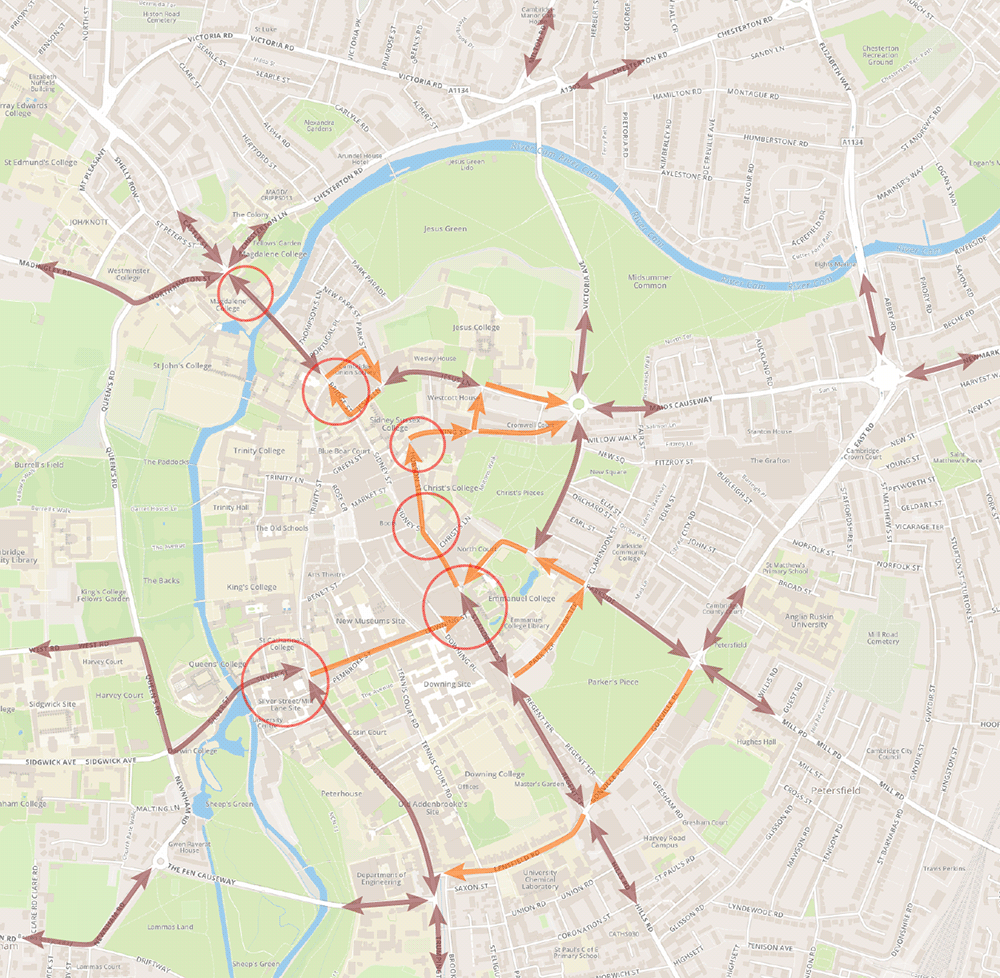

The central hub comprises a bus station with 11 bays, and another 15 dispersed around the surrounding streets in six locations. (The bus stop on Emmanuel Rd is included because it is the most central stop for the Busway A service; the ones on Parkside are used by the X5 Oxford–Cambridge and National Express intercity services.) Interchanging can involve a walk of up to 600m and crossing roads without designated, let alone controlled, crossing points. There is no central information point and no signage to guide people to the right stop.

Many buses are routed to and from the central hub via narrow streets, bounded by historic buildings, including Magdalene College (started in the 15th century), Round Church (started in the 12th century), St Botolph’s Church (started in the 14th century), Queens’ College Old Hall (started in the 15th century) and Christ’s College (started in the 15th century).

Buses sweep over pavements at corners, obstructing pedestrians and making them – especially those with impaired vision – feel unsafe. In several locations, people cycling have to wait or get on the pavement to let an oncoming bus pass. Pollutants (especially particulates and nitrogen oxides) build up in narrow streets, exposing people to dangerously unhealthy concentrations. The weight and vibrations caused by 15 tonne buses damage the roads and surrounding buildings.

Future growth in population, mainly in settlements beyond the green belt, and in employment sites around the city will require a large expansion in the frequency and coverage of bus services into the city – potentially tripling inside ten years. The current bus hub has little capacity to absorb that growth, and more buses in the city centre would further degrade people’s experience of walking and cycling in the city.

What are the alternatives? Hubs have an essential role in enabling people to interchange. It’s not possible to run public transport services from every village and suburb to every destination (employment site, school, shop, leisure facility, etc.) So the success of public transport is largely dependent on making it easy and intuitive for people to complete a journey with a change of mode or vehicle, e.g. walk → bus → bus → walk, or cycle → train → bus → walk.

Types of bus hub

There are two types of hub designs that facilitate interchanging between services, enabling people to reach multiple destinations quickly and easily:

- Hub-and-spoke: Services connect at a specific location (‘hub’), usually a central terminus. Preston or Swansea bus stations are pre-eminent examples of large, purpose-built bus stations in the centre of a city.

- Ring-and-spoke: Services follow a circular route (‘ring’) within or around the city, so that interchanging is possible anywhere around the ring. Oldenburg is a pre-eminent example of this, with all bus routes going via the inner ring road rather than the city centre.

Hub-and-spoke routing

Hub-and-spoke routing works where the bus station:

- is well-connected to the road network;

- has space for enough bays for the peak rate of arrivals, departures and layovers;

- is compact and well-signed, allowing for quick and easy connections.

Cambridge currently uses hub-and-spoke, but fails on all three accounts:

- The hub is connected to congested and narrow streets, which hold up buses unpredictably and compete for space with people walking and cycling.

- Emmanuel St gets congested, indicating that there is little spare capacity to increase the number of services, which will present a problem in coming years. By a rough estimate, we will need bus services to convey three times as many people in ten years’ time.

- The hub is spread across several streets, requiring walking up to 600m and crossing roads to make a connection. Signage is largely lacking, and it would be challenging to rectify this in such a complex environment.

The managing director of Stagecoach East has proposed relocating the Drummer Street bus station to the south-east corner of Christ’s Pieces, where currently there is a bowling green. The proposed design includes twenty bays and access at both ends (from Drummer St and Emmanuel Rd). The land currently used for the bus station would be returned to Christ’s Pieces in a land swap. From purely functional point of view, this would be more efficient. However it does not address the problem of the limited capacity of access roads, and their unsuitability for large volumes of large buses. It also doesn’t provide capacity for significant growth in bus services in and out of the city.

Another option is to have multiple hubs around the city. Possible sites include: Cambridge railway station, Addenbrooke’s bus station, Cambridge North station, Grafton Centre on East Rd, and Sun Street. These sites are well-connected to only one or two radial routes, and are not evenly distributed around the city. There is neither the space at all the sites, nor would it be operationally efficient, to serve all destinations from every hub; therefore many journeys would require two changes, adding delay and inconvenience.

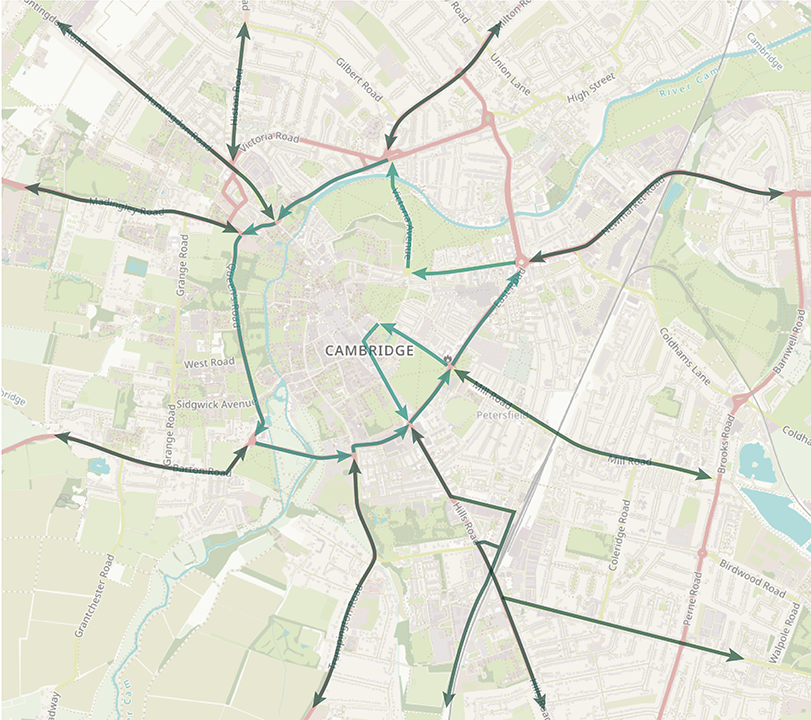

Ring-and-spoke or ‘lollipop’ routing

Ring-and-spoke or ‘lollipop’ routing could work well in Cambridge because there is an inner ring road close to the city centre. The most intuitive way to run buses is counter-clockwise, so that doors open towards the city centre. Some buses would still enter the city centre via Parkside, Emmanuel St and Regent St. Some of the benefits include:

- To reach any destination in Cambridge requires at most one change of bus anywhere on the inner ring road.

- To interchange between buses entails walking no further than the length of two bus bays, and does not require crossing a road.

- More of Cambridge would be within easy walking distance of a high frequency bus service, making bus travel attractive to many more people in the city. This reduces car traffic and increases demand, and hence revenue, to run the buses.

- Removing bus – and potentially all large vehicles – from the city centre opens up opportunities to widen pavements, add cycle lanes, and pedestrianise more of the city centre.

- Many streets would see a renaissance, either because they become more attractive places to be (e.g. Hobson St, King St, Round Church St) or to get to (e.g. the Grafton Centre, Sun St, Chesterton Rd).

There are however some disadvantages that need to be taken into account (which we cover later):

- Bus turn-around time (between reaching the inner ring inbound and leaving it outbound) is slower than going in and out of central Cambridge. This makes services slightly less cost efficient.

- Bus drivers need to lay over at the outer end of their route rather than in central Cambridge.

- Queen’s Rd and The Fen Causeway will carry many more buses than they do now.

Tackling congestion

How could this work when the inner ring road is so congested in places at peak times? We consider three possible solutions here:

- Make the inner ring road one-way clockwise for general traffic, and buses only counter-clockwise.

- Introduce access controls to divert general traffic, perhaps just at peak times, onto alternative routes.

- A congestion charge that disincentives using the inner ring road at times when it would be congested.

1. One-way system

Route all express buses counter-clockwise (so that doors open towards the city centre), with all other traffic required to run clockwise. In other words, the inner ring road becomes one-way clockwise with a contraflow bus lane.

The ring road is 6.5km in circumference. At an average speed (including stops) of 22km/h (13.5mph), a complete circuit by bus would take 18 minutes. (The assumed speed is taken from Singapore, where buses encounter relatively little congestion. It assumes that dwell times at stops are minimised through efficient ticketing, clear and accurate information provision, and use of two-door buses).

There would be at least one bus stop between each major junction (with a radial road). If each bus stop on the route has three bays, it will be possible to accommodate 180 buses per hour, each stopping for up to one minute.

Pros for bus users

- Buses gain the speed and reliability benefits of an inner city bus lane without any requirement to widen roads.

- Much more of the city is directly accessible by bus.

- Almost all of the city is accessible with just one change of bus at any point on the inner ring road.

- If no other motor vehicles are permitted to use the bus lane, then delays caused by parked vehicles (in particular, taxis and delivery vans) causing an obstruction will be rare.

- Smart Traffic Management could ensure that buses are held for a minimal amount of time at junctions, reducing journey times.

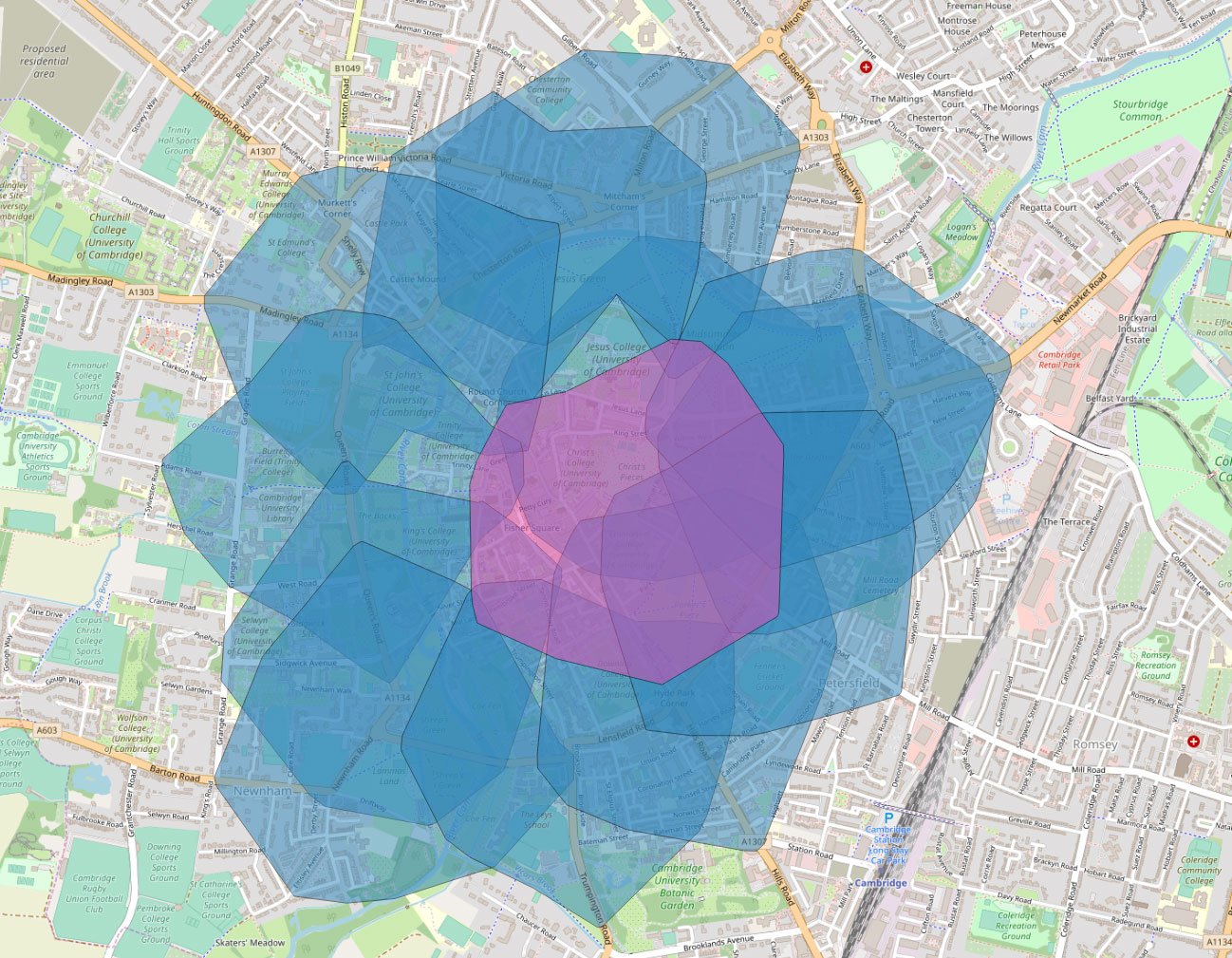

- All of the centre of the city is within 600m of the inner ring road (an 8 minute walk at a leisurely 4.5 km/hr or 2.8 miles/hr). Stops on Emmanuel St would be closer, but would serve fewer destinations directly (e.g. Cambridge station and Addenbrooke’s).

- People can choose where on the inner ring road to alight and board to reduce either walking distances or bus journey times.

Other pros

- No road-widening is required.

- One-way systems are easy to sign and understand.

- It would be possible to trial the change with temporary road signs and traffic lights.

- Non-bus traffic will flow more smoothly because of the limited movements at each junction, with few vehicles making right turns.

- This in turn makes it easier to give more time and priority at junctions to people walking and cycling.

Cons

- Some trips by car require a detour, but never be more than 6.5km (4 miles or about 15 minutes) and typically much less.

- If cycles are permitted in the bus lane, this will delay buses. A separate cycle lane or alternative (similarly direct) cycle route would ideally be identified for all parts of the inner ring.

2. Access controls

The objective is to divert traffic away from the inner ring road where a reasonable alternative route exists.

This might be achieved by restricting access along certain sections of the inner ring road, using ‘virtual bollards’ (monitored by automatic number plate recognition cameras). Locations to consider include Northampton St (with traffic diverted via Lady Margaret Rd and Mount Pleasant) and Lensfield Rd (with traffic diverted via Brooklands Ave). Map 4 illustrates these and other possible locations.

Access through these points, known as ‘bus gates’ would be restricted to buses, cycles, and certain other permitted motor vehicles, including emergency services. Other vehicles, such as taxis and certain low-emission commercial vehicles, could also be granted access, possibly on payment of an annual fee.

Another option to divert traffic is to restrict what turns are permitted at junctions on the inner ring road. For instance not turning between Hills Rd and Lensfield Rd in either direction would force non-bus traffic to use Brooklands Avenue instead. (The ‘rat run’ via Bateman St would also need to be blocked.)

Pros

- Some improvement to bus journey times and reliability on most parts of the inner ring road.

- Relatively easy to trial each intervention in isolation or together.

Cons

- Far less effective than a continuous bus lane in giving buses an unobstructed run around the city.

- Confusing for drivers unfamiliar with the restrictions or new to the area.

- Part-time access rules are complex to explain and sign.

- Bus gates require multiple signs to warn people not to proceed or make a turn that could lead them to an active bus gate.

- Some access restrictions needed to reduce congestion could require general traffic to make a long detour.

3. Congestion charge

Charge a daily access fee (‘road pricing’ or ‘congestion charge’) for any private vehicle using or crossing the inner ring road. However it cannot be introduced quickly at a price level that would eliminate congestion on the inner ring road, and there is a chicken-and-egg problem of improving bus services first to the point where people have a credible alternative to driving.

Pros

- Some improvement to bus journey times and reliability on most parts of the inner ring road.

- Raises revenue which could be invested in public transport, to subsidise bus ticket prices and/or provide more services for more hours at a higher frequency than would be commercially viable.

Cons

- Far less effective than a continuous bus lane in giving buses an unobstructed run around the city.

- Confusing for drivers unfamiliar with the congestion charge.

- Variable pricing or time-dependent charging is difficult to communicate, but a flat fee (as in London) is likely to be regarded as unfair and overly burdensome on those who need to drive.

- Expensive to trial, as it requires monitoring, payment systems and enforcement to be fully operational.

Conclusion

Acess controls would not eliminate congestion, and would not reduce it at all on some parts of the inner ring road (e.g. The Fen Causeway). However, some access or turn restrictions would complement a one-way system to promote smooth traffic flows and discourage or prevent rat-running through residential areas.

Some form of road pricing has a role to play in future, as we will cover in a future paper. However, trying to introduce it before people can see that bus services have been radically improved is likely to be politically difficult and undoubtedly slow.

The one-way system solution is the most elegant solution. It’s also technically and politically the easiest to trial and, following a successful trial, to implement.

The benefits of a ring-road bus hub

The principal benefit is the greater intuitiveness of the bus network and ease of interchanging.

A high frequency service around the inner ring road brings much of the city centre within a 15 minute bus ride and walk. Areas that are currently neglected would be revived: for instance, Burleigh St and the Grafton Centre, Newmarket Rd around Sun Street, and Chesterton Rd.

Removing buses from the city centre frees up space for people, making it possible to widen pavements and add cycle lanes. It would make it easier (practically and psychologically) for people to access the city’s green spaces, such as Jesus Green and Christ’s Pieces. That latter could be connected to New Square in a much more pedestrian-friendly way.

There would be no need for any road widening, or other infrastructure to work. Pollution levels would fall dramatically in the city centre. Medieval buildings in the city centre would no longer be affected by the damaging impact of large numbers of heavy vehicles.

Appendix: answers to questions about the ring-road bus hub

How would this affect me when I need to drive in the city?

Traffic signals would make clear to road users which turns are permitted at each of the junctions on the inner ring road. At the Catholic Church junction, for instance, Hills Rd inbound traffic would be permitted only to to turn left; outbound traffic would be permitted to go straight on or turn right. Filter arrows on the traffic lights would make this clear.

People would still be able to park their cars at the multi-storey car parks for the foreseeable future (in part because the City Council is heavily dependent on the revenues from these car parks). Streets within the inner ring road would still be accessible for residents, buses (with size/weight restrictions on roads between Emmanuel St and Magdalene St) and licensed taxis.

Won’t this require people to make long detours to drive across the city?

The ring road is 6.5km in circumference. Driving at an average speed of 25km/h (16mph), a complete circuit would take 15 minutes. 50% of trips would be unchanged if the ring road were one-way. Only 17% of trips would be 10–15 minutes longer following the ring road, and most of those could be shortened by choosing a different route.

The question is whether adding no more than 15 minutes to a small percentage of trips is a fair and reasonable imposition.

There isn’t a solution that will make it no less convenient to drive and better for buses. Improving bus reliability requires a reduction in car traffic. That will incentivise more people to use buses and ensure they experience a better service. More people using buses makes it possible to run more frequent services to more places for more hours of the day. That makes taking the bus a viable, even attractive, alternative to driving. This is the virtuous cycle we need to set in motion.

How would this affect emergency services?

These would have use of the bus lane (as well as the general traffic lane), so they would benefit from having an uncongested route around the city at all times of day.

How would this affect deliveries?

All parts of the city would continue to be accessible. Companies providing commercial services, from deliveries to boiler maintenance, can plan routes for their vehicles that follow the direction of flow of the inner ring road, minimising wasted mileage. In most cases, re-ordering visits would ensure that the total journey time was no greater than now.

Cycle couriers will continue to have the advantage of being able to travel along access-restricted streets in the city centre.

Won’t this require people to walk much further than now?

For most trips, the answer is no – for two reasons: firstly, people can get off and re-board wherever on the inner ring road is closest to where they’re going or returning from. For many trips that will involved less walking than now.

Secondly, other services will provide additional connections: high frequency shuttle services between the city centre, Cambridge station and Addenbrooke’s via Gonville Place will offer people the option to go to/from Emmanuel St; and small electric buses would run through the city centre, providing a similar service to the courtesy bus at Addenbrooke’s (see Local services (city) in our paper on Buses).

There will of course be some trips that require a longer walk than now or a transfer to a local service. But this should be considered alongside all the places that will be much more accessible than now, such as the Job Centre on Chesterton Rd, the Grafton Centre, West Road Concert Hall or the Scott Polar Museum.

All parts of the city will be within a 600m walk of a stop on the ring road. To put this into perspective, that’s about the distance from the Trumpington Park & Ride bus stop outside John Lewis to the front of Great St Mary’s Church; or from the Drummer St bus station to the entrance to the Grafton Centre. This is the upper limit on walking distances; most destinations will be much closer to a bus stop.

In addition to having an inner city shuttle service, we would hope to see shops in the city offering to deliver purchases to people’s homes or pick-up points (like Amazon Lockers) at community centres, Park & Ride sites, travel hubs, and other locations.

How will this affect me cycling around the city?

Cycling around the inner ring road will always be unappealing and relatively unsafe because of the volume of traffic. In some places, for instance along Gonville Place, there is sufficient road space to provide segregated cycle lanes by removing filter lanes or central reservations. Elsewhere, the priority should be to develop a continuous network of cycle routes within the inner ring road that obviates the need to cycle on the ring road itself. The removal of buses, and possibly also taxis, from, for instance, Bridge St and Hobson St, will make these more attractive for cycling.

The simplification of movements that vehicles can make at junctions on the inner ring road makes it easier to design junctions with more frequent pedestrian crossing phases and to provide an advance green phase for people cycling.

How will it affect my journey time?

One of the tools we need is a future journey planner that allows people to compare a trip now, by car or bus, based on observed journey times, with the same trip in the proposed scenario. It would then be much clearer who would benefit and who would lose out. If every before-and-after trip that people test is stored and evaluated together, then it would be much clearer what the social benefits and penalties would be.

Would cycles be permitted in the bus lane?

By default cycles are permitted to use bus lanes. However this would slow down buses. Therefore, wherever possible, cycle lanes should be accommodated outside the bus lane.

Would taxis be permitted in the bus lane?

Normally taxis are permitted to use bus lanes. However, they impede buses when they stop to pick up and drop off. If taxis are permitted to use the inner ring road bus lane, then it should be on condition that they may not stop in the bus lane or on the adjacent pavement.

Where would taxis wait?

There needs to be a separate debate about where taxis should wait, and which streets they can access when. For instance, it might be desirable to exclude taxis from the city centre during the day, in order to create a more pedestrian-friendly environment. In which case, the rank on St Andrew’s St might move, permanently or just during the day, to Emmanuel St, in place of some of the bus bays.

What about long distance services?

National Express and other long-distance services could occupy vacated bays at Drummer St bus station. Other options should be considered in the longer term, for instance terminating services at hubs, such as Park & Ride sites adjacent to the A14 and M11, if and when those are also linked to the city centre by a metro.

Where would bus stops be located?

The exact locations would need careful consideration and consultation. Some are fairly obvious, such as at the back of the Grafton Centre.

A possible location on Queen’s Rd (The Backs) is just south of the West Rd junction, where there are currently pay-and-display parking bays.

On Lensfield Rd, the existing bus stop location, just east of the Trumpington Rd junction, could be used. The road there is currently three lanes wide (the centre lane is hatched), so there would be space for buses to pass each other.

What would the bus stops look like?

There would probably be three sawtooth bus bays at the edge of the road (as on St Andrew’s St), mostly close to junctions with radial roads. Ideally they would have bus shelters. Where there is space, they would have a bank of short-hire bikes close by.

Could the one-way system be peak times only?

The simpler the system, the easier it is for people to understand and the better it will work. Congestion can occur at any time of day. Stopped delivery vehicles and taxis frequently block traffic. If we are serious about making buses a highly attractive alternative to driving, we need to keep other traffic out of their way.

Where would the pedestrian crossings be?

There should be a pedestrian crossing close to every bus stop. Locating bus stops close to junctions with light-controlled crossings is the simplest way to achieve this. Unlike zebra crossings, light-controlled crossings can be programmed to operate smartly: when a pedestrian presses the call button, if a bus is approaching the lights do not change until the bus has passed; otherwise they change immediately, so long as a minimum time has elapsed since the pedestrian phase was last active.

How many buses would be circulating the inner ring road?

A best guess would be that, in ten years time, the number of buses running at peak times around the inner ring would be between 100 and 150/hour. During the day and evenings, it would be closer to 50/hour.

Currently about 130 buses arrive in the Drummer St area bewteen 8am and 9am on a weekday. There is spare capacity on those buses, but a combination of modal shift and growth in population and employment will mean that the total number of buses required to move everyone around will grow significantly.

Between 2012 and 2017, there was a 13% increase in personal trips into Cambridge. On current growth trends, an additional 27% can be expected over the next ten years. Assuming that trips made by walking, cycling and train all increase by 27%, then we are left with about 25,000 additional daily trips that will need to be made by means other than driving.

The current best growth forecast for employment in the city in 2031 is that it will be between 32% and 82% higher than in 2011 (based on research at the University of Cambridge). We have used 27% growth to 2028 on top of 13% growth from 2012, which equals about 44%, so comfortably within the forecast range.

On top of that, the Greater Cambridge Partnership has an objective to reduce traffic in the city by 10-15% from 2011 levels. This would decongest the city centre, enable buses to move freely, and improve air quality. But it means shifting another 20,000 daily car trips to other modes.

Taken together, that means getting an extra 45,000 daily trips into Cambridge to be made by train, bus, cycling or walking – on top of expected growth in number of people walking, cycling and taking the train. Cambridge North and South stations will absorb some of that; as will improvements to cycling infrastructure. But a large proportion of that extra demand will have to be absorbed by buses. Even just 50% of those 45,000 trips equates to a near tripling of bus services.

A large proportion of those buses would not circulate the inner ring road at peak times. Some services would terminate at the Biomedical Campus and railway stations. Some would shuttle between the Biomedical Campus, Cambridge station and the city centre via Gonville Place. At peak times, some services would run from major settlements via the A14 and M11 to major employment sites, such as the Biomedical Campus and Science Park.

This shows how the flow of buses on the inner ring relates to the frequency of services on the nine radial roads into Cambridge:

| Frequency on radial road | Frequency on ring road | Distance between buses | Carrying capacity* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6/hour (every 10 minutes) | 54/hour (every 66 seconds) | 400m | 4,590 people/hour |

| 12/hour (every 5 minutes) | 108/hour (every 33 seconds) | 200m | 9,180 people/hour |

| 15/hour (every 4 minutes) | 135/hour (every 27 seconds) | 165m | 11,475 people/hour |

| 20/hour (every 3 minutes) | 180/hour (every 20 seconds) | 120m | 15,300 people/hour |

*Seated and standing capacity, assuming a 50:50 mix of single-decker (capacity 70 people) and double-decker (capacity 100 people) vehicles, averaging 85 people/bus.

Won’t this be detrimental to The Backs?

Routing buses along Queen’s Rd, alongside The Back is one of the more controversial aspects of the proposal. To be be clear exactly what is proposed:

- The northbound lane continues to carry general traffic.

- The southbound lane carries buses only.

- Car parking is removed from Queen’s Rd as this could not be accessed safely from the northbound lane (cars would be manoeuvering in and across the bus lane).

- Unless and until a new location is found for a coach drop-off, coaches also use the southbound lane and continue to use the coach stopping bays at the southern end of Queen’s Rd.

- Bus stop bays could be located to the south of the West Rd junction, where currently there are car parking bays.

- The design of the bus bays would be a task for professional designers. For minimal visual impact, the bus bays could simply be marked in paint on the road (as the parking bays are currently), with three poles marking the stops. An electronic information board could replace the parking ticket machine.

- No part of the road would need to be widened.

Queen’s Rd is one of the busiest and most critical arterial roads in the city. Also known as the A1134, it is part of the city’s inner and (incomplete) outer ring roads. The average daily amount of traffic (last counted in 2016) is:

- 13,102 cars

- 221 buses/coaches

- 1,728 LGVs

- 143 HGVs

- 307 motorcycles

- 15,501 motor vehicles in total

The only way to reduce the volume of traffic on this road is to reduce it across the entire city. That requires shifting people from cars to alternatives, including buses. The object of routing buses around the inner ring road is to facilitate that modal shift.

The views of the Backs and King’s College Chapel are mostly enjoyed from the paths and meadows on the east side of Queen’s Rd, where traffic does not interrupt the views. Views from the road are mostly obscured by parked cars; they would not be under this proposal.

With an average spacing between buses of between 120m and 400m (see above), the visual impact is arguably less than the current stream of traffic and parked vehicles. A bus occupies the road space of two moving cars, yet replaces a queue of up to sixty cars, stretching from Burrell’s Walk to Silver St. It can also be argued that giving bus passengers access to this uplifting view on their way to work is a boon.

There is an argument for running only single-decker buses in Cambridge, but this would entail running more buses at peak times, and increasing ticket prices.

When considering the negatives of running buses along Queen’s Rd, it’s important to also consider the negatives of continuing to run ever more large, heavy buses through Bridge St, Magdalene St, Jesus Lane, King St, Hobson St, St Andrews St, Silver St and Trumpington St. Not only are they a visual eyesore in the city centre, they are damaging our built heritage: college buildings and churches dating back hundreds of years.

Could buses use Grange Rd instead of Queen’s Rd?

The additional distance alone would add 20% (3–4 minutes) to the journey time to circulate the inner ring. At peak times though the delay would be significantly greater, because all buses would have to mix with general traffic on a stretch of Madingley Rd, and either West Rd (if buses were just excluded only from the stretch of Queen’s Rd north of West Rd) or Barton Rd and Newnham Rd. The junctions at the Fen Causeway and Northampton St would also operate less efficiently because flows of buses and general traffic would be crossing and merging. This would undermine the benefits of having buses circulate the inner ring road without obstructions.

There is also a pinch point on Grange Rd between the Cambridge University Rugby Club and Robinson College, where the road is not wide enough (at 5m) for two buses to pass. This would further delay buses, and create conflict with people cycling.

It was decided some time ago that traffic should be deterred from using Grange road, presumably because schools and halls of residence front onto it.

Is there also a proposal for a separate cycle lane along Queen’s Rd?

There is a need for an alternative cycle route between west Cambridge and the city centre that avoids Garret Hostel Lane and Senate House Passage, as that route is often heavily congested during the summer, making conflicts and collisions inevitable. However this is a separate issue to running buses along Queen’s Rd, and the need for a solution is not altered by whether or not buses are routed along Queen’s Rd.

How will lost parking on Queen’s Rd be replaced?

The aim of reorganising buses is to make them more convenient and attractive for more trips throughout the day, for instance to attend a public lecture at the Sidgwick Site or a concert at West Road. Hence demand for parking spaces will fall.

What about the noise and pollution created by buses?

Buses will soon be electrically-powered. Shenzen in China runs a 100% electric fleet of buses: 16,359 of them. The whole-life cost of an electric single-decker bus is now almost the same as for a Euro 6 (low emission) diesel bus. Once that is also true of double-deckers, it will be in operators’ commercial interests to buy electric fleets. The Greater Cambridge Partnership is already working on plans to install the necessary charging infrastructure.

How will this meet the needs of an aging population?

Public transport has a critically important role in allowing people to retain their independence, maintain their social connections, and continue being active. This redesign of the bus network is intended to make buses work better for everyone.

The design of buses does need to adapt to changes in society, and that includes providing better accessibility for people with impaired mobility, with young children, and carrying shopping or luggage. More space is needed to accommodate wheelchairs, strollers, push chairs and luggage. Two-door buses facilitate speedy boarding and disembarking, and hence reduce dwell time at stops. By using optical or magnetic guidance into bus stops, it is possible to align buses precisely with the kerb, making level boarding possible.

We need to incentivise bus designers, builders and operators to invest in making buses a fit form of transport for everyone. We also need to design bus stops and shelters to enable level boarding for two-door buses.

Wouldn’t a congestion charge be better?

A congestion charge would deter people from driving in the city, but people will still need to make those trips and will therefore require a viable alternative to driving. A congestion charge goes hand-in-hand with running more buses.

Shouldn’t we wait until the metro is built?

There is not yet a detailed costed plan for any part of a metro. Such a project will be hugely ambitious for local authorities with no experience of commissioning anything like it before. An optimistic timetable would be for the first metro line to be running in ten years. By itself one line will only serve a fraction of the population. So we need to do something radical with buses to get us through at least the next ten years of population and employment growth.

If and when we get a metro running through tunnels under the city, it will be possible to re-plan the bus network, with some services terminating at metro stations, where people would transfer to reach certain city destinations. But there will always be a need for buses to reach the large majority of the city that will not be within easy walking distance of a metro station. In other words the metro and buses will complement each other.

Why route buses into the city centre when the jobs growth will be outside?

It is true that future jobs growth is focused on areas around the city: Biomedical Campus, Science Park, Cambridge station, West/NW Cambridge, Cambridge North station, Northern Fringe East (sewage works), Airport (Marshalls industrial sites and, probably at some point in the future, the airport itself). Even if public transport delivers most employees to those sites without traversing the city (but see the answer to the next question), there will still be growth in demand to travel into and around the city.

Much of the ‘knowledge intensive’ work that goes on in Cambridge involves inter-company meetings. This will contribute to continued growth in trips from Cambridge railway stations to London, Stansted Airport and elsewhere. People working at those sites will want to travel into the city to shop, socialise, enjoy the culture, access health services. So too will people living in new settlements outside the city. Tourism too will continue to grow.

We’re already behind the curve in public transport provision. Rail capacity is being increased to the south, but is severely constrained to the north and east. Bus provision is being reduced almost everywhere except the Guided Busway. This is pushing more and more people to drive, even people who previously used public transport.

Wouldn’t it be better to run buses along an outer orbital?

Cambridge doesn’t have a complete outer orbital. The two most significant gaps are across Grantchester Meadows and Ditton Meadows. Some buses will run along orbital roads, especially at peak times when demand is high and the route is most direct, for instance:

- Cambridge North station to West Cambridge via Darwin Green and Eddington

- Cambourne to the Science Park via the A14

- Cambourne to the Biomedical Campus via the M11

- Teversham to the Biomedical Campus via Airport Way to Queen Edith’s Way

In general though, outer orbital routes are not efficient for public transport: the distances are longer; they serve fewer significant destinations; and offer fewer opportunities to interchange. Many journeys have more than one destination (e.g. a school, a workplace, a shop, a restaurant), which are more likely to all be reachable within a reasonable journey time via the inner ring road.

There are some estimated comparative journey times for inner and outer orbital routes in the appendix to our response to the Cambourne–Cambridge busway consultation.

Won’t people still prefer to drive than take the bus?

Improving bus services in the city centre is only one of a raft of measures needed to rebalance the incentives for people to use sustainable modes of transport. Other measures include:

- Reducing parking availability in the city centre, for instance with neighbourhood parking schemes.

- Prioritising buses on radial routes, for instance using Inbound Flow Control.

- Making parking in the city more expensive, for instance with increased charges to arrive or depart from multistorey car parks at peak times; increasing on-street parking charges; levying a tax on staff parking spaces provided by employers.

- Some form of road pricing or congestion charging.

- Improving train services by adding new stations and reinstating track on the Newmarket line.

- Running more express bus services from travel hubs throughout Cambridgeshire.

Isn’t Park & Ride a better solution

Park & Ride doesn’t reduce the number of buses in the city centre, only the number of cars. However there are many reasons why it is preferable to develop a comprehensive bus network that serves the rural community directly, rather than via Park & Ride sites.

Where would buses lay over?

Buses currently terminate on the city and there is a delay before it must leave again as the next outbound service. This is timetable ‘recovery time’ to compensate for variable delays inbound. This proposal assumes that buses will run at a fixed frequency rather than to a timetable, at least at peak times. The Traffic Commissioners’ office does not require a timetable for ‘high frequency services’, defined as every ten or fewer minutes.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to preserve headways to avoid bunching (e.g. 2 buses followed by a 20 minute wait), which entails holding some buses back for a few minutes. A few locations on the inner ring road offer an opportunity for that without disrupting other buses: Grafton Centre, Sun Street, Victoria Avenue, Chesterton Road. It may also be possible to take buses out of service to lay over in the bus station or on Parker St or Parkside.

[Graphics updated 13 October 2019]